Multithreading is one of the most popular C++ topics today — and also one of the hardest to get right.

Concurrency bugs are notoriously difficult to reproduce, and when they happen, they often lead to painful debugging sessions and fragile fixes.

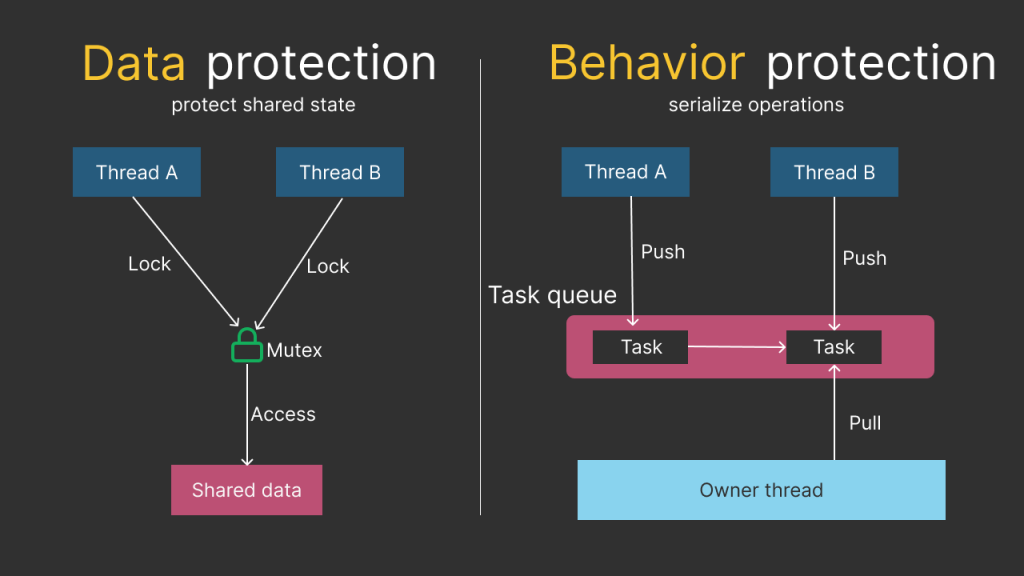

At a high level, there are two common strategies to protect your code from concurrency issues:

- Protect the data (guard shared state directly).

- Protect the behavior (serialize operations so the state is touched in a controlled way).

Both approaches aim to prevent data races and keep invariants intact — but they have very different trade-offs. In this article, we’ll compare them and discuss when each one makes sense.

Protect data against concurrent access

The C++ standard requires that shared state is accessed in a way that prevents data races.

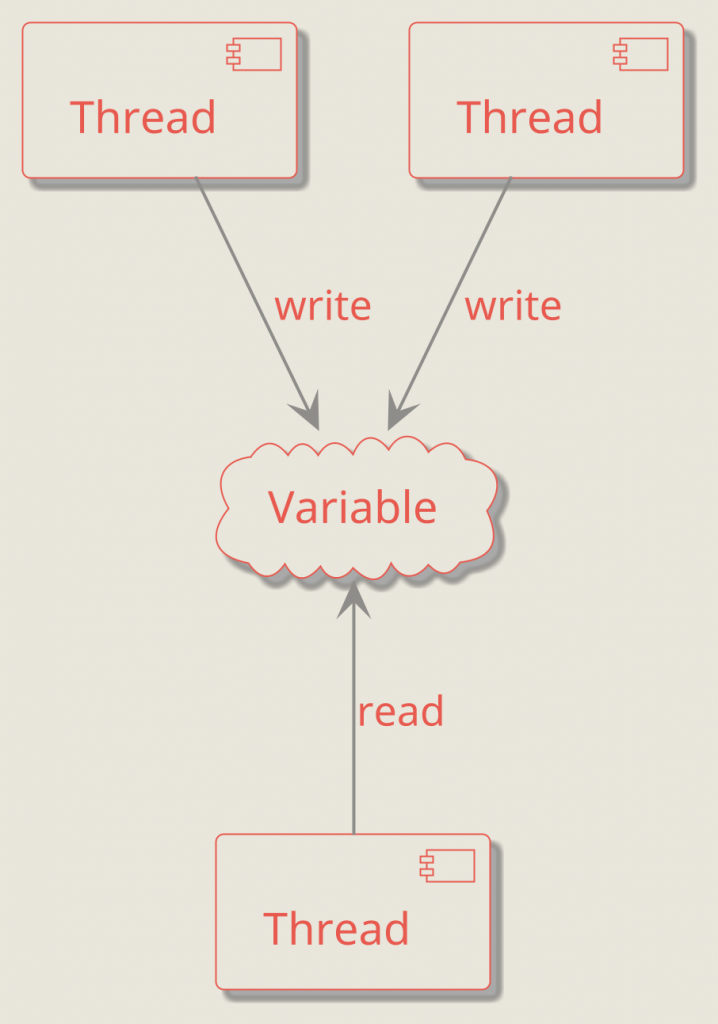

A data race happens when two threads access the same memory location concurrently, at least one access is a write, and there is no synchronization establishing a happens-before relationship between them. If that occurs, the program has undefined behavior:

This is what data protection is about: using synchronization primitives such as std::mutex (mutual exclusion) or std::atomic (well-defined concurrent access) to ensure correct coordination between threads.

In many cases, data protection is straightforward. For example, if several threads share a single variable—some write to it while others read—then that variable must be accessed through a mutex or an atomic type (depending on the requirements).

To ensure data integrity, shared variables must be accessed using synchronization primitives such as mutexes, atomic variables, or other mechanisms that prevent data races.

Why is this necessary?

While the standard defines the rule, the underlying reason is that both the compiler and the CPU are free to perform aggressive optimizations:

- the compiler may reorder reads/writes or keep values in registers,

- the CPU may execute operations out of order,

- cores may observe memory updates at different times due to caches and store buffers.

Without synchronization, there is no guarantee that one thread will observe another thread’s writes in a consistent or timely manner—and the standard intentionally treats such programs as undefined.

Example: protecting a class invariant with a mutex

class Foo {

public:

void write(std::string name) {

auto lock = std::lock_guard{m_mutex};

m_name = std::move(name);

}

std::string read() const {

auto lock = std::lock_guard{m_mutex};

return m_name;

}

private:

mutable std::mutex m_mutex;

std::string m_name;

};

In this example, std::mutex ensures mutual exclusion: only one thread can read or write m_name at a time.

Just as importantly, the lock/unlock operations also provide synchronization: an unlock() in one thread synchronizes-with a successful lock() in another thread, establishing a happens-before relationship between the critical sections. That’s what makes the read see a consistent value.

Note: returning m_name by value is a good choice here. Returning a reference would leak the protected object outside the lock, which defeats the protection.

Why protecting data is harder than it looks

Protecting shared data looks straightforward when the access pattern is simple: lock a mutex → read/write → unlock.

But in real systems, it quickly becomes tricky.

Many concurrency bugs don’t come from a single field access. They come from breaking an invariant that spans multiple fields.

Even if each field is “protected”, you still have to ensure that compound operations happen atomically. In practice, that often means:

- locking around multiple reads and writes,

- sometimes locking multiple mutexes,

- and being careful about lock ordering to avoid deadlocks.

If several threads operate on a complex object, the precondition for a correct operation is rarely “one read”. A single logical operation can involve a sequence of reads and writes, and those steps must not interleave with other threads in a way that breaks the object’s invariants.

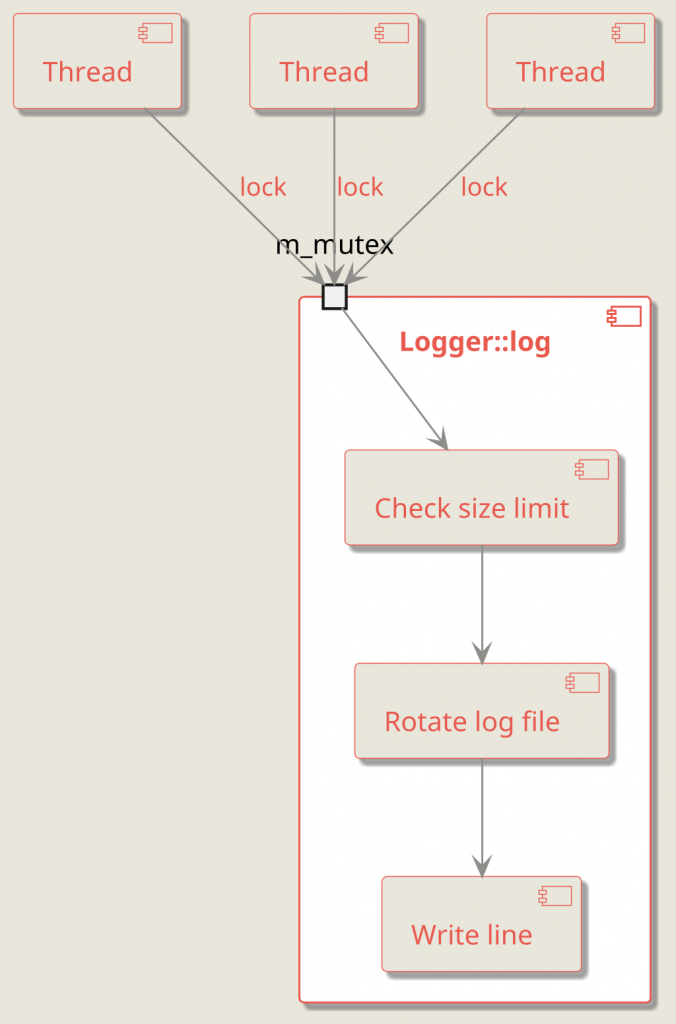

Example: a logger with file rotation

Consider a logging class Logger. One of its responsibilities is to enforce a maximum log file size. When the limit is exceeded, the logger closes the current file and opens a new one.

In a multithreaded environment, Logger::log() must run without interference from other threads while it checks the limit, possibly rotates the file, and then writes the line. Otherwise, the internal state may be corrupted—for example:

- the file could be rotated multiple times without actually exceeding the limit,

- the size counter could be updated incorrectly,

- output could end up in the wrong file.

A common solution is to lock a mutex at the beginning of the operation:

class Logger{

public:

void log(std::string_view line) {

// Lock the mutex and prevent this method

// being invoked simultaneously by multiple

// thraeds

auto lock = std::lock_guard{m_mutex};

// Check if the file size limit is exceeded

if(line.size() + m_size > m_maxLogSize){

// Close the current log file

rotateLogs();

m_size = 0;

}

m_out << line;

m_size += line.size();

}

private:

std::size_t m_size;

std::size_t m_maxLogSize;

std::ofstream m_out;

std::mutex m_mutex;

};

The diagram below shows what happens when multiple threads call Logger::log() at the same time: only one thread enters the critical section, while others wait:

At this point, the mutex is not protecting a single field from concurrent reads/writes—it’s protecting the entire operation (the behavior) from interleaving. In other words, you’ve moved from data protection to behavior protection.

This approach is effective, but it can also make the codebase more error-prone. During refactoring, it’s easy to accidentally move a read or write outside the critical section, reintroducing subtle bugs.

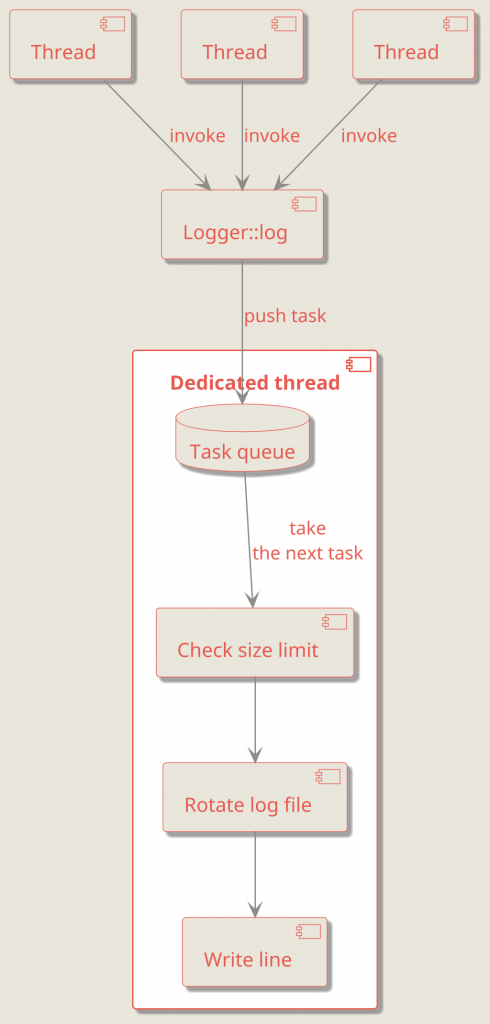

Protecting behavior

A different way to handle concurrency is to protect behavior rather than shared state.

Instead of letting multiple threads call methods directly (and relying on every caller to lock correctly), you serialize all operations on the object by executing them in a controlled context—for example:

- a dedicated worker thread, or

- a task queue (actor-style model).

In this model:

- callers don’t touch the internal state directly,

- they submit work,

- and the object processes tasks sequentially.

The key benefit is that there is a single, clear owner of the mutable state—the worker thread—and all modifications happen on that thread.

In many cases, delegating work to a dedicated thread via a task queue is cleaner and less error-prone.

For example, a Logger::log call can enqueue a “write this line” task instead of writing to the file immediately. The worker thread then takes tasks from the queue and executes them one by one. That way, all logging operations are effectively synchronized because they run on a single thread, as shown below:

Since all logging operations are executed on the same thread, there’s no longer a need for a mutex inside the logger.

Instead of relying on “everyone must lock correctly”, this approach gives you a single owner of the mutable state: the worker thread.

Libraries like Boost.Asio (or Qt) are a good fit here. For example, with Boost.Asio you can implement a logger like this:

class Logger {

public:

Logger()

: m_work(boost::asio::make_work_guard(m_service))

, m_thread([this] { m_service.run(); })

{}

~Logger() {

m_service.stop();

}

void log(std::string_view line) {

boost::asio::post(m_service, [this, s = std::string(line)] {

// Executed on the dedicated thread.

if (s.size() + m_size > m_maxLogSize) {

rotateLogs();

m_size = 0;

}

m_out << s;

m_size += s.size();

});

}

private:

boost::asio::io_context m_service;

boost::asio::executor_work_guard<boost::asio::io_context::executor_type> m_work;

std::thread m_thread;

std::size_t m_size = 0;

std::size_t m_maxLogSize = 0;

std::ofstream m_out;

};

This code has several important places:Key details in this code:

m_workkeepsio_context::run()from returning when the queue is temporarily empty.- The destructor stops the

io_contextand the thread joins automatically to shut down cleanly and avoid leaks.

One important trade-off: writes happen asynchronously. If the program exits right after submitting many log lines, shutdown may block while pending tasks are processed (unless you explicitly drop/flush/cancel them).

With this approach the code is often much easier to reason about: callers just submit tasks, and all state changes happen on a single thread.

Conclusion

Both approaches solve real problems — but they optimize for different things.

- Protecting data gives you flexibility and can be highly performant, but it relies on the caller consistently following locking rules. As systems grow, that discipline becomes harder to maintain.

- Protecting behavior reduces the surface area for concurrency mistakes by serializing access and encapsulating synchronization inside the component — at the cost of overhead and reduced parallelism.

A practical rule of thumb:

- If you need maximum concurrency and your locking rules are simple and local → protecting data is fine.

- If you want stronger safety guarantees, fewer footguns, and clearer APIs → protecting behavior (e.g., actor-style) can be the better design.

In many production systems, a hybrid approach works best: keep low-level, performance-critical parts data-locked — and build higher-level components around behavior-serialization to keep the architecture robust.