Mutexes are verbose, lack composability, and can easily lead to deadlocks. Worse, these problems are often hard to reproduce and debug.

An alternative approach is transactional memory.

Transactional memory is an old idea designed to simplify concurrent programming. Instead of carefully managing locks, developers describe atomic blocks of work, while conflict detection and rollback are handled by the runtime.

Despite its age, transactional memory has seen limited adoption. In C++, it is available primarily through GCC’s implementation, based on the N1613 proposal published back in 2011.

Transactional memory is an elegant concept — but today it remains more of an experiment than a production-ready tool.

In this article, I’ll explore GCC’s transactional memory support, explain how it works, and show how you can write concurrent code using it in practice.

All code examples from the article are available here: https://github.com/sqglobe/transaction-memory

What Transactional Memory Is

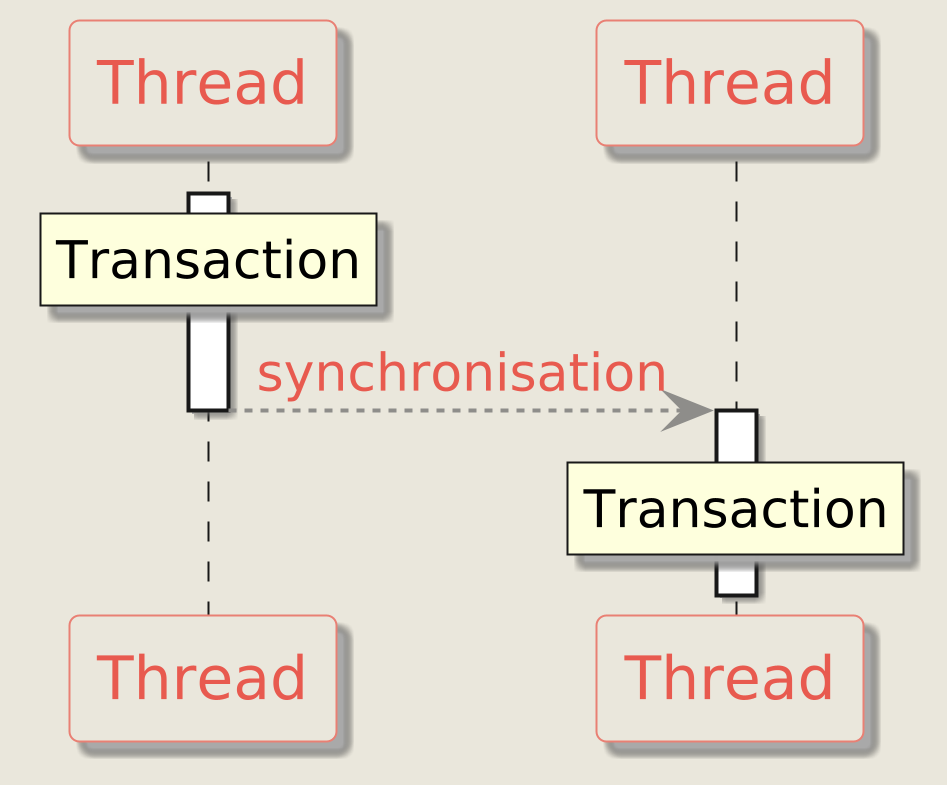

Transactional memory provides a high-level approach to synchronization in concurrent programming

by enforcing atomicity, consistency, and isolation for code sections marked as transactions.

A transaction is a block of code that either completes fully or has no effect at all.

Intermediate states are never visible to other threads.

Let’s consider a simple example of a bank account represented by the Account class,

which provides two operations:

put— deposits money into the accountwithdraw— withdraws money from the account

class Account {

public:

Account(std::size_t current);

public:

bool withdraw(std::size_t amount);

void put(std::size_t amount);

private:

std::size_t m_current;

};

A common operation on such accounts is transferring money from one account to another.

The function returns true if the transfer succeeds and false otherwise:

bool transfer_money(Account& from, Account& to, std::size_t amount) {

if (!from.withdraw(amount)) {

// Not enough money in the source account

return false;

}

to.put(amount);

return true;

}

If this function is executed as a transaction, it runs atomically and in isolation.

Either both accounts are updated, or neither is changed.

No other thread can observe an intermediate state where the from account

has already been updated but the to account has not.

Which Problems It Solves

Using low-level synchronization primitives such as mutexes comes with several well-known drawbacks.

- Granularity and verbosity

Fine-grained mutexes typically protect individual shared variables (or small groups of variables).

To read or modify such data, the corresponding mutex must be explicitly locked. As a result, the program structure becomes harder to reason about and more error-prone— especially when a developer forgets to acquire the correct lock. To read or modify such data, the corresponding mutex must be explicitly locked.

As a result, the program structure becomes harder to reason about and more error-prone— especially when a developer forgets to acquire the correct lock. - Deadlocks

Mutex-based designs can easily lead to deadlocks.

These bugs are often difficult to reproduce and debug, and even small mistakes in lock acquisition order or missing unlocks can break the program. - Lack of composability

Lock-based synchronization does not compose well.

Even if individual operations protected by mutexes are correct, their combination may still be unsafe.

For example, if each Account object is internally protected by its own mutex,

composing two accounts into a transfer_money operation requires additional synchronization

to avoid races or deadlocks.

Transactional memory addresses these problems by shifting synchronization responsibility from the developer to the runtime. Transactions are executed in a global order: a transaction only commits once all conflicting transactions have completed.

Instead of juggling multiple mutexes, the developer simply marks code that accesses shared state as a transaction, and the runtime ensures proper synchronization.

Important note: Accessing a variable shared across multiple threads outside of a transaction is considered a data race and results in undefined behavior.

When To Use It

A transaction is executed atomically: either all updates are applied, or none of them are.

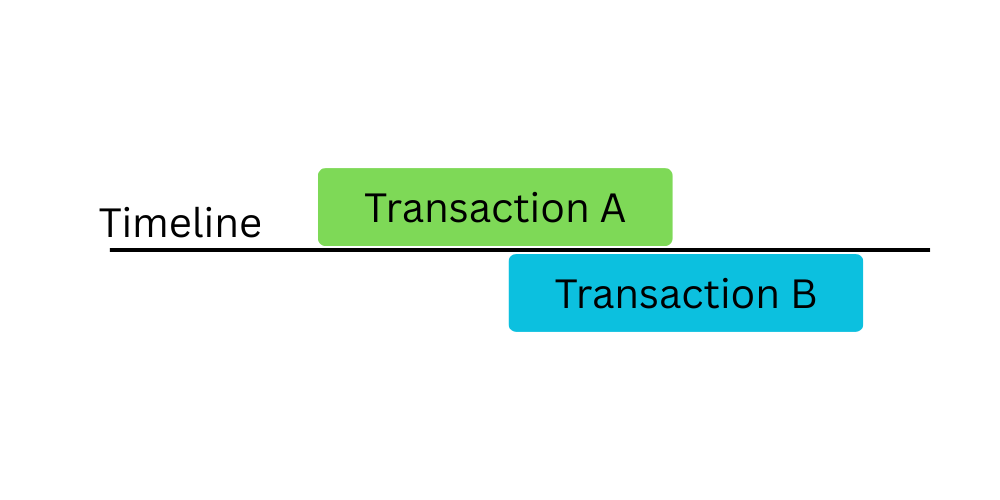

The runtime may execute multiple transactions in parallel as long as they do not modify the same variables.

In case of a conflict, one of the transactions is aborted and restarted.

This is how optimistic concurrency control works.

When conflicts are rare, transactional memory can efficiently utilize CPU cores and make concurrent code clearer and easier to reason about than fine-grained mutex-based synchronization.

However, rollbacks come with a cost. If conflicts are frequent, performance can degrade significantly.

I would consider using transactional memory only when:

- operations must be atomic across multiple objects

- rollback semantics are required

- conflicts are expected to be rare

- code clarity is more important than raw performance

Like any other C++ concurrency feature, transactional memory has its trade-offs, and these must be evaluated carefully for each use case.

What You Need To Get Started

Transactional memory has been partially implemented in GCC since version 4.6.

To use it, you’ll need:

- A GCC version that supports transactional memory

- The

itmruntime library - The compiler flag

-fgnu-tm

Below is an example of how to enable transactional memory in CMake:

# Look for library `itm` that contains required symbols

find_library(ITM

NAMES itm itm.so libitm.so

PATHS /usr/x86_64-linux-gnu/lib/ /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/)

add_executable(examples main.cpp)

target_compile_options(examples PRIVATE -fgnu-tm)

target_link_libraries(examples PRIVATE ${ITM})

This configuration enables transactional memory support

for the examples executable.

Depending on your environment, you may want a cleaner or more portable way to locate the itm library — for example, by using find_package or a custom CMake module instead of hardcoded paths.

⚠️ Note: Transactional memory support in GCC is experimental and platform-dependent.

Expect limitations and incomplete diagnostics compared to mature synchronization primitives.

With the setup in place, we can now look at how transactional memory behaves in practice.

Simple Example With synchronized

If you need synchronization for a small number of operations across multiple threads, consider using the GCC extension keyword synchronized.

This keyword marks a block of code to be executed in a globally ordered, transactional manner — meaning no two synchronized blocks overlap in execution. Effectively, it provides atomicity and isolation without explicit mutexes.

Here’s a simple example of a thread-safe counter implemented using synchronized:

class Counter{

public:

int count(){

synchronized{

return i++;

}

}

private:

int i = 0;

};

Each call to count() executes the block atomically and in isolation, ensuring thread safety.

There are very few restrictions on what can be done inside a synchronized block. Pure computations work well, while operations with external side effects (e.g., I/O or system calls) may cause the transaction to abort.

Important: Accessing

Counter::ioutside of a transaction (i.e., withoutsynchronized) is considered a data race and results in undefined behavior.

You can find the complete implementation in the file: transactional.h on GitHub

In contrast to lock-based synchronization, there is no need for an additional class member to store a mutex, or for explicit lock and unlock logic. Compare this with a traditional mutex-based implementation:

class Counter

{

public:

int count()

{

auto lock = std::lock_guard{m_mutex};

return i++;

}

private:

std::mutex m_mutex;

int i = 0;

};

With transactional memory, you only need to mark a specific block as a transaction — the runtime handles the rest.

Rolling Back A Transaction

While synchronization is useful, an even more powerful feature is the ability to roll back applied modifications when a condition is not met.

Consider a function that transfers a specified amount of money from one account to multiple target accounts.

Now assume that the Account class has an additional constraint: Account::put may fail and return false if the account balance exceeds a predefined limit.

class Account {

public:

Account(std::size_t current, std::size_t max);

public:

bool withdraw(std::size_t amount);

bool put(std::size_t amount);

private:

std::size_t m_current;

std::size_t m_max;

};

If, during the transfer operation, Account::put fails for any target account, all previously applied transfers must be rolled back, and the system must return to the state it had before the function call.

This is a perfect use case for transactional memory.

To create a transaction block, use __transaction_atomic.

To explicitly roll back all changes performed inside the transaction, use __transaction_cancel.

bool transfer(Account &from, std::size_t amountPerAccount, std::vector<Account> &to){

const std::size_t total = amountPerAccount * to.size();

// Start the transaction

__transaction_atomic{

if (!from.withdraw(total)) {

// Rollback on error

// Control flow after this point

// goes directly to `return false;`

// statement

__transaction_cancel;

}

for (auto &account : to) {

if (!account.put(amountPerAccount)) {

// Rollback on error

// Control flow after this point

// goes directly to `return false;`

// statement

__transaction_cancel;

}

}

// Return from the transaction success

// The transaction is committed automatically

return true;

}

return false;

}

}

Note that __transaction_cancel transfers control to the first statement after the transaction block —

in this case, return false. This allows the failure result to be propagated to the caller naturally.

The function is available here:

https://github.com/sqglobe/transaction-memory/blob/main/examples/transactional.h

One important detail: __transaction_atomic blocks are globally synchronized, so no additional mutexes or atomics are required.

However, there are several important limitations:

- Functions called inside a transaction must be marked as transaction-safe,

or the compiler must be able to infer this. - No assignments, initializations, or reads from volatile objects.

- No inline assembly.

- All operations inside a transaction must be reversible —

no file writes, no socket communication, and no other irreversible side effects.

Because transactions may be rolled back, the runtime can apply optimistic concurrency control.

This means that transactions are allowed to execute in parallel, and conflicts are detected at commit time. If a conflict is detected, one of the transactions is aborted and retried.

When conflicts are rare, this approach can achieve higher performance than lock-based synchronization due to reduced synchronization overhead.

Alternatives

For synchronization, you can use mutexes or atomic variables when working with individual types or small objects. This avoids the global ordering requirement and allows concurrent operations on unrelated data, which can significantly improve performance.

For operations that require rollback semantics, however, there are fewer general-purpose alternatives. Custom solutions can sometimes be faster and impose fewer restrictions, but they usually require more careful design and significantly more effort to implement correctly.

You can find alternative implementations for both the Counter class and the transfer() function in the following file:

https://github.com/sqglobe/transaction-memory/blob/main/examples/alternatives.h

Performance Compared

Let’s compare the performance of the transactional memory approach with an

alternative implementation. For benchmarking, I used Google Benchmark.

I ran both examples with different number of threads to identify how it affects the performance. One and fifty threads produce the following result:

| Number of threads | Transactional approach | Alternative implementation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Counter | 1 | 61.609 ns | 6.847 ns |

| 50 | 86.071.961 ns | 4.938.726 ns | |

| Account transfer | 1 | 182.302ns | 27.976 ns |

| 50 | 6.240.051ns | 11.102.064ns |

As you can see, for simple synchronization the std::mutex implementation is more than 9× faster than transactional memory with a single thread, and about 17× faster with 50 threads. As the number of threads increases, the performance of transactional memory degrades significantly.

On the other hand, in scenarios where operations may fail and intermediate results must be rolled back, the picture changes. For a single thread, the alternative implementation is still about 5× faster. However, with 50 threads, the transactional memory implementation becomes almost 2× faster due to optimistic concurrency control.

In this case, operations in different threads often work on physically independent objects, which reduces conflicts and allows transactions to proceed without synchronization.

That said, lock-based implementations could still be optimized further by introducing more fine-grained mutexes, which may improve performance.

In other words, transactional memory can make concurrent programming significantly simpler, but it comes with substantial performance costs. These costs are often unacceptable in performance-critical C++ applications, which is why transactional memory remains a niche tool rather than a general-purpose solution.

Conclusion

Transactional memory offers an elegant and expressive way to reason about concurrency.

However, today it remains more of an experimental feature than a production-ready tool for most C++ systems.

Limited compiler support, runtime overhead, and strict restrictions on side effects significantly limit its applicability.

Still, understanding transactional memory is valuable — it sharpens how you think about atomicity, isolation, and rollback in concurrent systems.