Practical techniques: forward declarations, moving implementations to cpp, and PIMPL — explained with real examples.

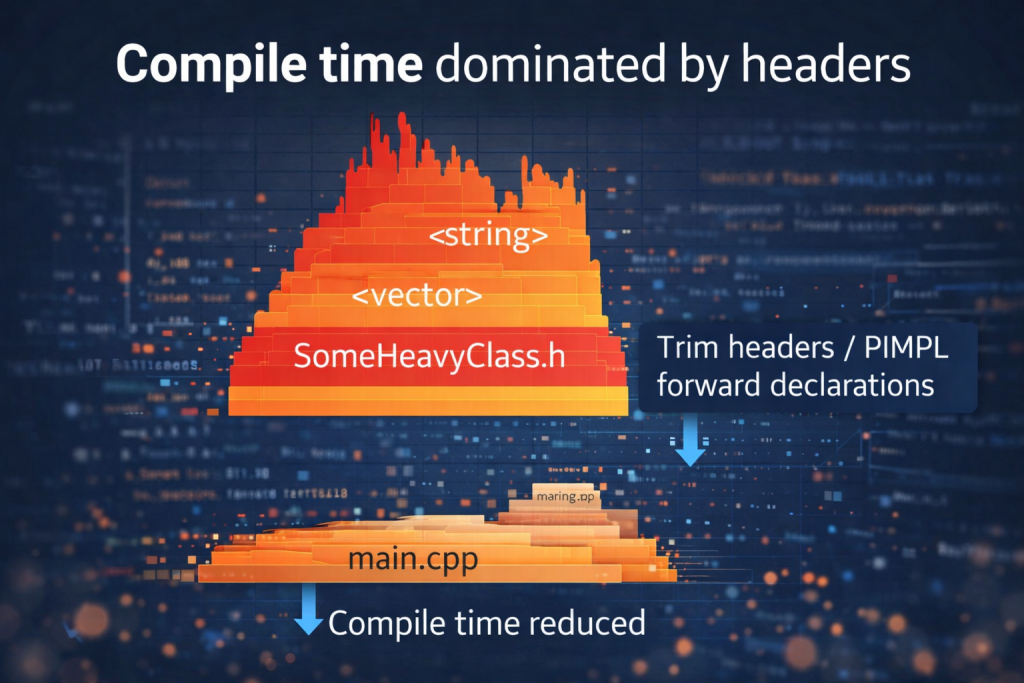

One major factor that can slow down compilation is headers. When they are too heavy or included in every translation unit, they can significantly increase compilation time.

In this article you’ll learn:

- why headers dominate compile time

- how to reduce transitive includes

- when forward declarations are safe

- when PIMPL is worth the cost

This article is not about compiler flags or build systems.

It’s for developers who want to understand why their build behaves the way it does.

How headers are processed

During the preprocessing stage, the preprocessor replaces each #include directive with the actual content of the referenced file for every translation unit. This process applies not only to direct includes but also recursively to all nested headers. The result is a large expanded source file, which is then analyzed, compiled, and optimized.

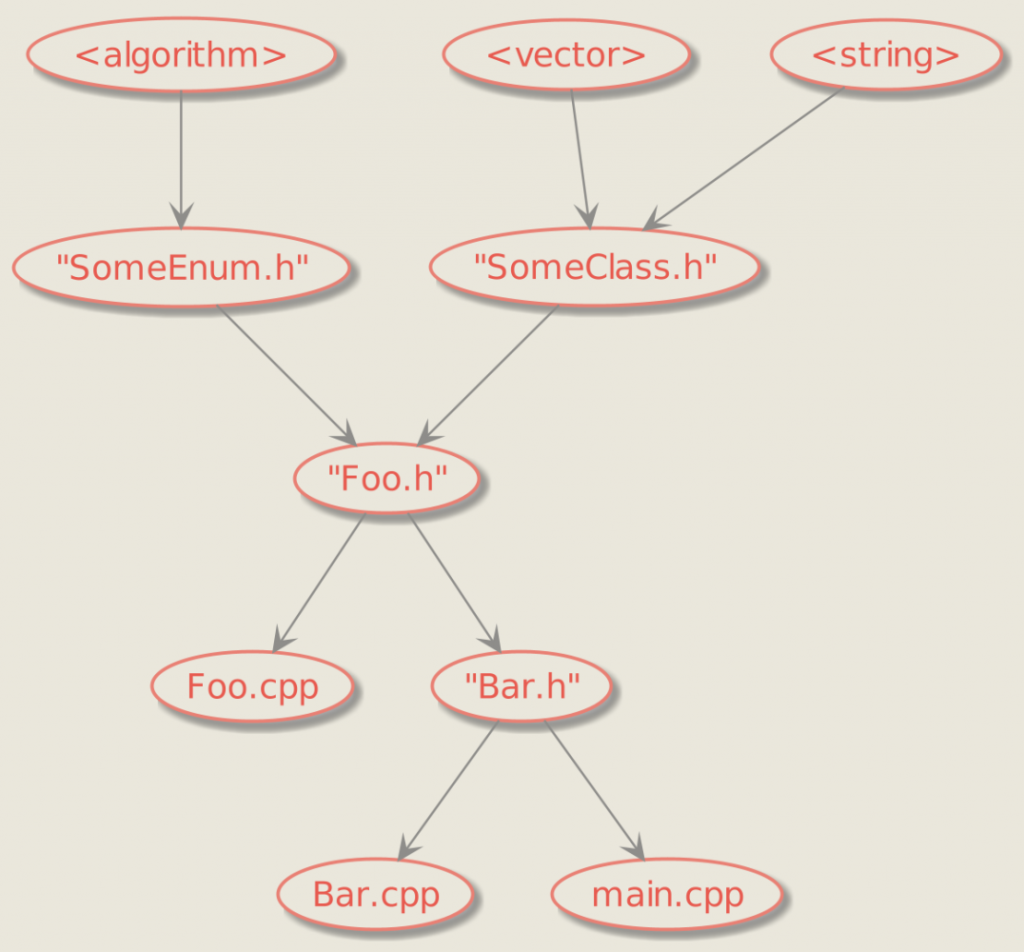

Consider the following include tree:

After preprocessing stage each of main.cpp, Bar.cpp and Foo.cpp will contain full content of SomeEnum.h and SomeClass.h, like in the following picture:

Thus, even a small optimization in a single header file can affect all translation units that include it, either directly or indirectly. And proper compilation time profiling helps you to find the most expensive headers to process.

Forward declaration

If something isn’t used—remove it. In some cases, a full type definition isn’t required. Such types can be forward-declared in the header file, and the corresponding header should be included only in the translation units where the type is actually needed.This approach differs from applying precompiled headers, when a file processed once and then the intermediate result is only reused.

Types that can be forward-declared include classes, structures, and enumerations. However, this is possible only if those types aren’t directly used in the header—for example, no methods are called, and no enumeration values are accessed. Essentially, forward declarations can be applied when a pointer to a class or an enumeration is stored as a member, used as a function return type, or passed as a parameter. This works because, at this stage, the compiler only needs to know the size of the pointer or the enumeration type.

Consider the following code in Foo.h:

#include "SomeClass.h"

#include "SomeEnum.h"

#include <memory>

SomeEnum foo();

std::unique_ptr<SomeClass> makeSomeClass();

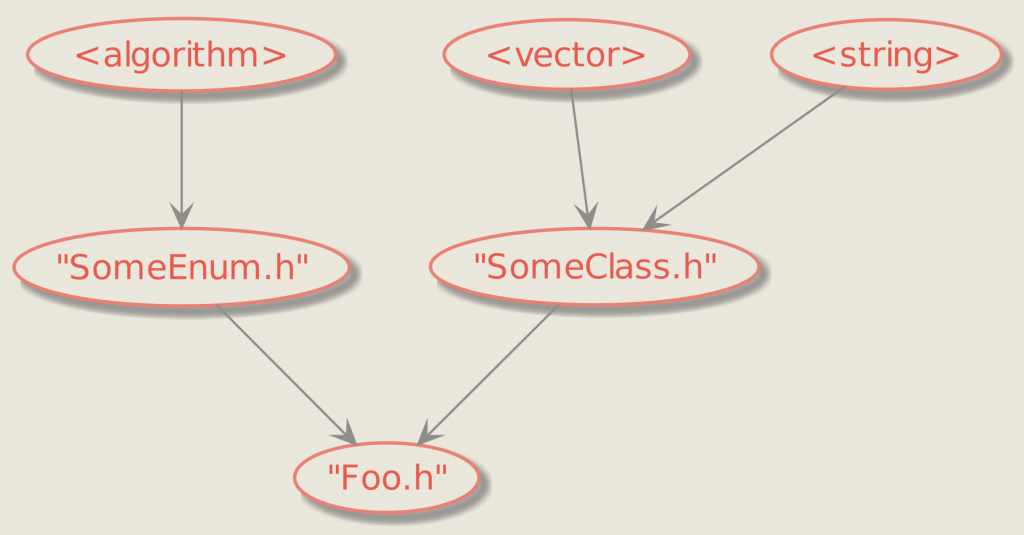

The include files tree might be represented with following diagram:

In this example, the enumeration SomeEnum is used as a function return type, and a smart pointer to the class SomeClass is also declared. Therefore, both can be forward-declared, and two include tree branches can be eliminated because the compiler doesn’t need to know the exact size of SomeClass or the values of SomeEnum.

After a small refactoring, all other headers or translation units that include Foo.h but don’t use SomeEnum or SomeClass no longer pay the cost of including their corresponding headers. The refactored Foo.h looks like this:

#include <memory>

class SomeClass;

enum class SomeEnum;

SomeEnum foo();

std::unique_ptr<SomeClass> makeSomeClass();

In this way, only the translation units that actually use SomeClass or SomeEnum need to explicitly include their respective headers. As a result, the number of transitive inclusions of SomeClass.h and SomeEnum.h can be significantly reduced.

Move method implementation into cpp file

Another useful idea is to move implementations and private functions from a header into a .cpp file. Such code often requires additional includes in the header, even though it isn’t used directly by any client. As a result, every translation unit that includes this header ends up paying an unnecessary compilation cost.

Consider Bar.h with the following content:

#include <string>

#include <algorithm>

#include <optional>

class Bar {

public:

bool hasValue(const std::string &value) {

auto it = std::find(m_container.begin(),

m_container.end(), value);

return it != m_container.end();

}

private:

std::optional<int> parseValue(const std::string &value ) const;

};

Several headers, such as <algorithm> and <optional>, are only needed for the method implementations. By moving the implementation of Bar::hasValue and the full definition of Bar::parseValue into the .cpp file, these two headers can be removed from the header:

#include <string>

class Bar {

public:

bool hasValue(const std::string &value);

};

In this way, translation units that include Bar.h but don’t use <algorithm> or <optional> will benefit from faster compilation.

Pointer to the implementation

The most significant technique is PIMPL (Pointer to Implementation), where the header contains only a pointer to a forward-declared implementation class, and all method calls are forwarded to that implementation. This approach hides the entire implementation, including all private members. It is especially useful when the original implementation requires heavy headers—for example, if your class inherits from a large class or contains one as a member.

Consider the following header:

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <atomic>

#include <mutex>

#include "SomeHeavyClass.h"

class Foo: SomeHeavyClass {

public:

void saveString(const std::string &str);

private:

std::mutex m;

std::vector<std::string> m_values;

std::atomic<int> m_uniqueValues;

};

There is a Foo class that inherits from SomeHeavyClass. That header is very large and takes a long time to process. The class cannot be forward-declared because the compiler requires its full definition due to the inheritance. A possible solution is to create an implementation class, Foo::Impl, forward-declare it, and then forward all calls from Foo to Foo::Impl. With this approach, the Foo class can be updated as follows:

#include <string>

#include <memory>

class Foo {

private:

class Impl;

public:

void saveString(const std::string &str);

private:

std::unique_ptr<Impl> m_impl;

};

In this way, the heavy header file is included only in Foo.cpp, where Foo::Impl is defined. This reduces the total number of includes of SomeHeavyClass.h and can significantly speed up overall compilation.

Summary

Compile-time optimization isn’t about flags or faster machines.

It’s about boundaries.

If your headers expose too much, every translation unit pays the price.

- Reduce includes

- Move implementations

- Hide what doesn’t need to be visible.

This is one of the problems that looks small — but shapes how large C++ codebases age over years.

This article is part of a larger series on real-world C++ engineering — the same mindset I’m developing in my book and monthly newsletter – From complexity to essence in C++